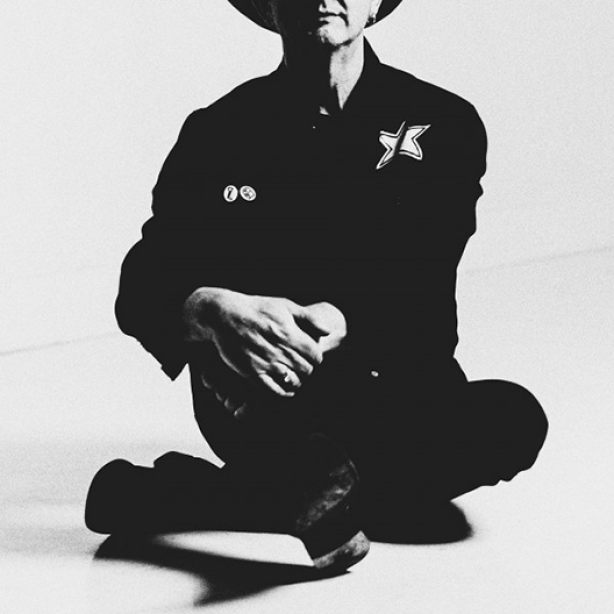

The day that Andy White’s world turned upside down.

As the Belfast-born star comes home for a gig, he tells Ivan Little of the pain

following the break-up of his marriage.

In his teens, Andy White used to hide behind a pillar on the stage of Belfast’s Errigle Inn because in the eyes of the law he wasn’t old enough to be playing his music there. But the singer/songwriter won’t be shying away from anything as he returns an older and wiser man to his cherished stomping ground from his new home in Australia later this month.

In his teens, Andy White used to hide behind a pillar on the stage of Belfast’s Errigle Inn because in the eyes of the law he wasn’t old enough to be playing his music there. But the singer/songwriter won’t be shying away from anything as he returns an older and wiser man to his cherished stomping ground from his new home in Australia later this month.

The 51-year-old sometime poet will be showcasing an album called How Things Are, which is full of new songs which he wrote about the breakdown of his 19 year marriage — a split that wasn’t of his choice.

Just listening to the intimate lyrics is hard for an outsider and it doesn’t take a febrile imagination to realise just how difficult it must have been for Andy to write the songs at a time when the pain of the collapse of his relationship was raw. But it was clearly his way of coping.

He says: “It was a very instinctive thing to do at the time. I was far from family and friends to talk to and instead wrote about it all in songs. I didn’t go back to them for quite a while and initially I thought about bringing them out in a double album, but this is the first chapter.”

Andy’s Swiss-born wife Christine told him that she wanted to start life again and that noone else was involved. In the songs Andy writes of his regrets and of “living in a brand new hell” in the aftermath of the break-up and of wishing she’d told him sooner.

One of the last lines he sings on the album is “I don’t make you happy — that’s the end of the story”.

In notes which accompany the record Andy writes: “She walked and I’d lost by best friend, lover and companion … Love at first sight? Yes that Romeo and Juliet moment does exist. I know how lucky I am that it happened. Even just once is amazing.”

The sentiments are obviously intense and highly personal for Andy, but he knows they’ll resonate with thousands of people who’ve been through a similar break-up. And, while the album may be wracked with sadness, it’s not from the Leonard Cohen wrist-slitting school of misery because Andy’s melodies — a mix of rock and acoustic folk — often belie the words.

“For me it is a kind of uplifting and beautiful thing as well as being a traumatic thing,” he says. “As soon as you put something to music it engages emotions in a really joyous and positive way and it is something that just telling the story couldn’t convey.”

It feels almost like an intrusion to ask Andy to talk in more depth about the marital difficulties that he’s put down in song but he’s willing, if not happy, to elaborate.

He says he didn’t see the end of the marriage coming. “It was really bad when it happened, but we are getting through it.”

The couple’s student son Sebastian lives in Melbourne with Andy and he sees his mother regularly. Sebastian was born in Belfast and lived with his parents in Dublin before they moved to Australia in 2002.

Away from his studies as a graphic designer, Sebastian, who travelled extensively with his dad on his musical journeys, is also a drummer. He first learnt to play on a little set of drums Andy bought for him in the Argos store in Great Victoria Street in Belfast for £9.99. He plays on the album which was recorded in Andy’s home studio — The Growlery.

“It was a real bonding experience,” Andy says. “It’s really just the two of us on the album, apart from Domini Forster, who added strings. Looking around to see my son playing the drums was a really big deal.”

But wasn’t it tough for him to contribute to an album charting the end of his parents’ marriage?

“As a drummer he didn’t focus in on the lyrics. Drummers mainly concentrate on the feel of the song,” Andy says.

Andy feels totally at home in Australia but doesn’t know if it will always be home.

He says he always thought he would return to Ireland, but adds: “It looks good in Australia at the moment”

Andy visited there after he formed a group called ALT with former Split Enz and Crowded House musician Tim Finn and ex-Hothouse Flower singer Liam O Maonlai. The permanent move came later.

“I’ve never had a real plan about where to go and what to do,” he says. “I just go with the flow and follow the opportunities. Dublin was becoming too expensive to live in. And things were happening in Australia for me and we decided to move to Melbourne. I liked the idea of Sebastian having the chance of growing up in a summery outdoor life.”

Another major break was his collaboration with Aboriginal singer Christine Anu on Coz I’m Free, a song about iconic Australian 400m Olympic medal winner Cathy Freeman, which was performed at the Sydney games.

Still, coming back to Belfast is always special for Andy. “I can’t wait to come home,” he says. “And the Errigle holds a myriad of memories.”

Not only did he take refuge behind that aforementioned pillar so that no one would catch on that he was underage as he played bass guitar in the upstairs music lounge, but his music-teacher grandmother also lived just a few doors away from the Ormeau Road pub.

“Part of my childhood was spent in her house,” says Andy.

Another outstanding memory is of seeing Van Morrison singing a couple of songs with James Brown’s All Stars in 1984. He had played support for Van on his No Guru, No Method, No Teacher tour of the British Isles a couple of years previous to this. He admits the Belfast singer was a huge influence on him and there’s a nod to Morrison’s music on a song called Separation Street on the new album.

“I grew up with Moondance and Astral Weeks and they’re really deep inside me. I listened to Astral Weeks last week with tears in my eyes,” he says.

“The way Van puts Belfast street names into his songs was just as inspiring as punk groups having their records played by John Peel.

“I always wanted to do that too, to be proud of the names. It doesn’t have to be Memphis or Sausalito. It can be Carrickfergus and Ballymena if you want it to be. And you can make it feel like poetic reality wherever you are and reach out and touch people’s hearts.”

Recently, Belfast came to Melbourne in the shape of the premiere of the Terri Hooley biopic Good Vibrations, which was written by Andy’s “oldest and closest” friend and former Methody

schoolmate, Glenn Patterson, who along with Colin Carberry, has received a BAFTA nomination for the screenplay.

“They asked me to write a piece for the introduction of the film and it was a real honour,” Andy says. “I remember I was on the steps of Good Vibes when I was 14 or 15. It was almost too cool for me to go in but I used to queue up to get autographs.”

He adds: “I was knocked out by the film. I was 10,000 miles away but it took me

right back to Belfast. The crowd went crazy for it.

“And for me it was particularly special because my son Sebastian was there too. I was delighted that he could see a little bit of what life was like in Belfast in the ’70s’ and ’80s.”

Andy, whose father Barry was an acclaimed writer for the Belfast Telegraph, says he had a “lucky up-bringing” in the midst of the Troubles but adds: “They did affect everyone.”

Andy was writing poetry from the age of nine and it was influenced by what was starting to happen on the streets of Northern Ireland. He left to study and graduated from Cambridge in 1984.

His first single in 1985, Religious Persuasion, was his early take on the Troubles. The punk revolution in Belfast had shown young singers like Andy that they didn’t have to go to Los Angeles to record their music. Instead, he went to Randalstown.

“Punk gave me and the group Therapy, who were also at the studios at the same time, the confidence that you could record for yourself in Northern Ireland.”

Religious Persuasion was eventually released by the revered Stiff Records label in England

and Radio One DJ Janice Long picked it up, playing it regularly on her show, which opened doors — and ears — across the UK.

His first LP — Rave On, Andy White — was also driven by his feelings about politics and violence here.

“I wanted to bring something beautiful out of the chaos,” he says. “That is what a lot of what art is about.”

Many of Andy’s subsequent 10 solo studio albums have also been autobiographical, ranging from his observations on his travels or his early days as a father.

But the response to the Troubles songs like Religious Persuasion still surprises him.

“I didn’t think they would mean anything to people outside Northern Ireland. But even if they don’t understand the words they can understand the attitude of it.”

Even now, nearly 30 years later, Andy still includes Religious Persuasion on his set-list because it’s such a crowd favourite. “I was taught that you should always sing the songs people want to hear,” he says.

Andy is keen to pass on his experience to young musicians in Australia and he’s been recording a number of them in his studio.

He’s happy, however, that his son has no plans to become a full- time musician.

“He’s lived in a musician’s family long enough to know that he’s going to have to choose something else,” Andy says. “I’ve always brought him up just to enjoy music and not to think about it as a career, though he would be good enough.”

Andy, whose sisters Cathy and Ali are actresses, has been spreading his creative wings with other artistic pursuits. He’s written two Lagan Press volumes of poetry and an often hilarious book called 21st Century Troubadour which, along with a double CD of the same name, is essentially an account of the good times and the bad times of a singer on the

road.

There’s preparatory work going on to turn Troubadour into a stage play and the Australian writer Kieran Carroll is confident that the show will hit the road.

“It’s a fantastic journey about the joys and hassles of gigs from Alaska to Italy,” says Kieran.

Andy is optimistic too, adding: “I’ve seen a first draft of the play. And it’s great. I would love it to be staged back home in Belfast. Which is where it all began.”

Andy White will be is playing at the Errigle Inn, Belfast, on Thursday, January 30. For details, visit www.errigle.com. His new album How Things Are, is released through Floating World Records on February 17

Ivan Little, 21 January 2014